- Algae

- Posts

- When old technologies were new - Sound, film and the year 1930.

When old technologies were new - Sound, film and the year 1930.

There's always precedence.

There is much we cannot see about change as it occurs. Historical readings are opportunities to reflect back onto a period when old technologies were new. What can we learn about change with the benefit of hindsight? Where do we even look? — These were some of the opening lines of my masters’ dissertation circa 2022.

I miss the days when digging up clippings of American Cinematographer Magazine and obscure fan magazines from the 1930s to analyze sound in cinema took up most of my time.

Not because I felt like an investigative sleuth, sleuthing away, which was arguably, a very enjoyable feat, but because making ambitious parallels where few dared to look taught me much about how contrasting perspectives are not only necessary but vital to studying technological turns in history.

I was in search of answers I knew probably weren’t as simple as “this changed the world” or “that created opportunity.”

Instead, the contradictions revealed a networked world, hidden to most but relevant to all.

Me, summer of 2022. This image is 100% accurate.

Relevant? Why?

Carolyn Marvin, professor of communication at Yale University writes that “new media intrude on negotiations by providing new platforms on which old groups confront one another.” 1 In October 2025, confrontation is certainly the word I’d use to describe contemporary discussions on creative technology.

Headlines such as Is AI necessary in art? Is it a waste of time? Or as critic Jerry Salz from Vulture scathingly wrote on artist Refik Anadol’s piece of AI art at the Museum of Modern Art — is it just a glorified screensaver? 2 Yikes. Harsh. But expected.

Sound discourse in cinema from the year 1930 shows us, representationally, at least, how new technologies are portrayed while being implemented into processes. Or even, why it matters that we look at discourse from a slice-of-pie perspective i.e. there are many ways to observe the same thing.

Setting the [sound] stage.

Donald Crafton, a prominent sound scholar has argued that “sound divides the movies with the assuredness of biblical duality.” 24 For Crafton, the transition was “years in the making and in the finishing.” There was not as much a clear before and after to demarcate when sound film 26 spread and the end of the silent film occurred.

There was a change, but when it happened and why, is up for debate.

Historians Robert C. Allen and Douglas Gomery describe film as a system rampant with multifaceted divisions across culture, art, economy, and technology. Within this system is a network. The question at hand — Was it also represented as “networked” during those years? Or again, do we only know this through benefit of hindsight?

Let’s take a look at some publications.

Speaking to the cameramen through American Cinematographer Magazine [ACM].

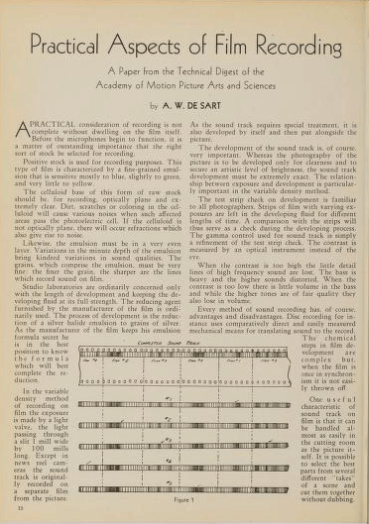

In a July 1930 edition of ACM, a writer named A.W. De Sart titled his piece “Practical Aspects of Film Recording.” He used the first-person voice to elaborate on the science behind the differences sound-on-film and sound-on-disc recording.

While the science itself isn’t relevant, the way it was communicated might show us how a craft like cinematography, which was also new, was being affected by the introduction of a newer technological system.

This of De Sart’s piece as a how-to-guide of 1930.

A digital archive print of A.W. De Sart’s piece on film recording.

That other guy.

“Both had advantages and disadvantages,” De Sart claimed. 3 One would need to choose the right stock. The celluloid base of the stock “must be clear and optically plane such that there are no refractions and noise.” 4 He then goes on to mention the process of development in the reduction of a silver halide emulsion to grains of silver while pointing out that the best person to know such a formula would be the manufacturer of the film who “keeps his emulsion formula secret.” 5

Although he began the piece with technical advice, De Sart was still not the ultimate expert. He was a conduit. He was a piece in a network, one that now involved a manufacturer of silver halide emulsion.

Basically, to get the full picture, you’d need to talk to ‘that other guy.’

Groups transact.

Marvin states that “old habits of transacting between groups are projected onto new technologies that alter, or seem to alter, critical social distances.”6

The existing relations embedded within cinematography, specifically between cameraman, equipment, director and environment were being questioned if not disrupted. While the technology was mediating this disruption, the transacting was happening between social groups.

So how did the cameramen feel about it?

Scathing, indeed.

In February 1930’s issue of ACM, a former ace cinematographer and officer of the ASC 12 named Bert Glennon wrote a scathing criticism of the talkies/sound films. 9Unironically, the subheading read “Some Honest Criticism by a Former Cameraman.”

Placed at the forefront of the magazine, Glennon began his piece by declaring the following–

“...in the thirty-odd years through which cinematography has grown from a laboratory experiment to its present commanding position among the artistic crafts, it has never been in a more anomalous nor a more dangerous position.”

A digital archive print showing a headline by Bert Glennon.

In a “great maze” of “ohms, watts, amps and thoughtlessness” Glennon believed that, while on the one end, cinematography had reached great mechanical perfection, it was artistically stunted through the year 1929.8 Almost nonchalantly he argued that the “new element of sound” and its “bewildering array of new apparatus” was upsetting everything.

Underneath Glennon’s criticism was a plea for the value of cinematography. At the core of his argument was a call to prioritize the visual by framing sound as a detractor from high standards. But it also implied a complex and bewildering apparatus, to use his language — a network upon a network disrupting a network. Cinematographers would now be required to make new negotiations in the adoption of a new system, one that indicated a change to the old one.

So, a how-to-guide + a scathing criticism — Which was it? A new technology to learn and get ahead or a dangerous turn? Or perhaps both?

Microphones, noise and the sound rush.

In an ACM issue of October 1930, technical director of sound at Pathe Studios L.E. Clark penned a technical digest paper from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences titled “Sound Stage Equipment and Practice.” 13

The following quote highlights the complexity of this stage:

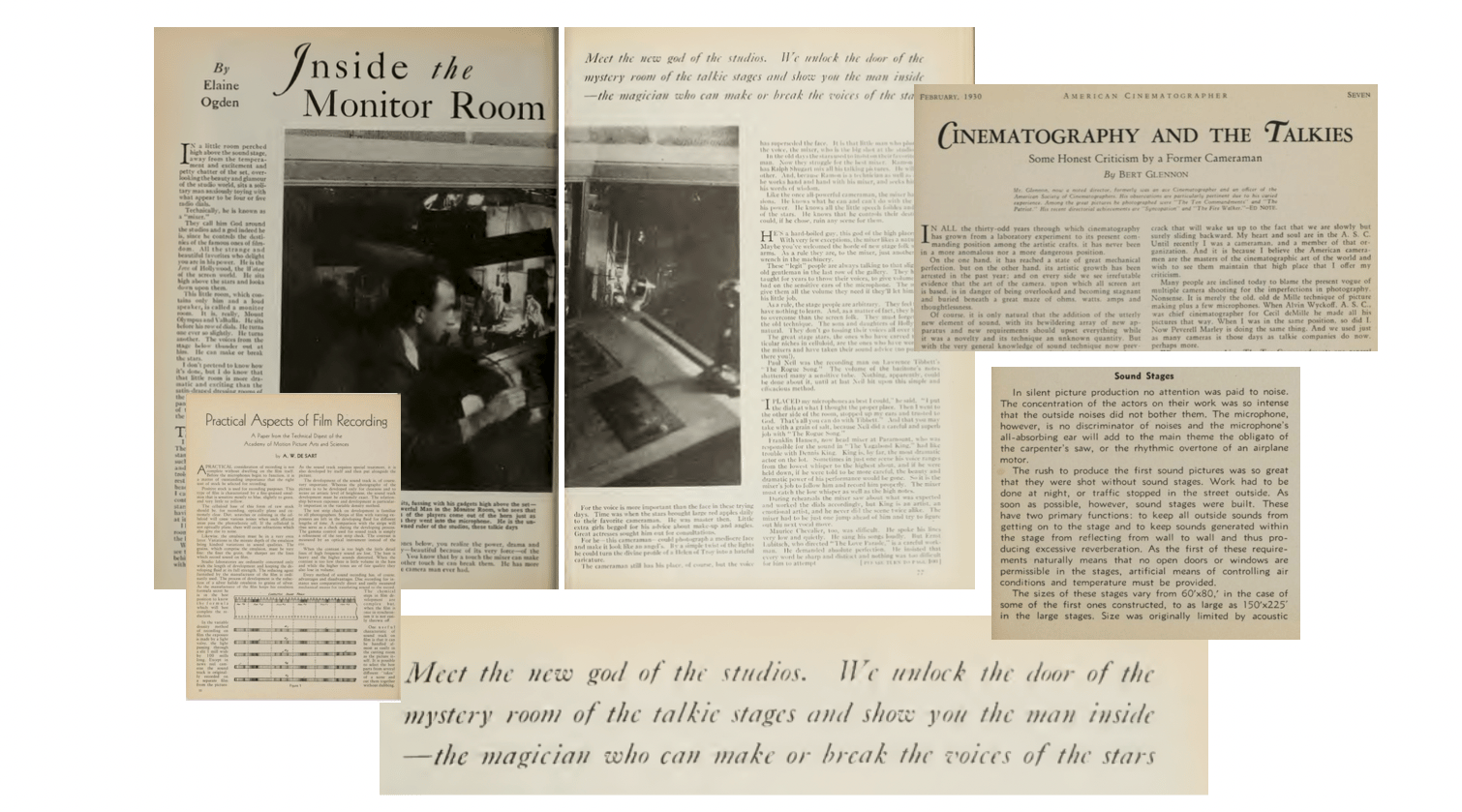

“In silent picture production no attention was paid to noise. The concentration of the actors on their work was so intense that the outside noises did not bother them. The microphone, however, is no discriminator of noises and the microphone's all-absorbing ear will add to the main theme the obligato of the carpenter's saw, or the rhythmic overtone of an airplane motor...The rush to produce the first sound pictures was so great that they were shot without sound stages. Work had to be done at night, or traffic stopped in the street outside.” 25

Original text from October 1930 ACM issue on sound stages.

Paying attention to noise meant that a new environment would need to be constructed in order to accomodate a new system. Or, as the quote states, filming would have to be done at night or only when traffic was low. Either way, a disruption was here. New considerations were paramount.

What began with the introduction of a microphone now involved a far more complex array of considerations — both spatial and temporal.

So what was the point of introducing sound if it only meant more complexity?

Let’s take a look at this excerpt from High Gray’s 2005 translation of renowned French film critic and theorist André Bazin’s What Is Cinema Vol. 1 —

“The reality produced by the cinema at will and which it organizes is the reality of the world of which we are part and of which the film receives a mold at once spatial and temporal.” (Bazin, 13)

For Bazin, in the mind of the inventor, one finds an innate desire to create exactness of the world around them or the “spatial and temporal mold.” Bazin argued that there was a “myth of total cinema” i.e. cinema’s beginning and end point is a reproduction of reality. 14 The history of film therefore also moved towards a total and complete representation of reality. 15

If sound in film was a move to total reality and reproduction of reality was the goal of cinema, then the disruptive consequences were inevitable.

The point was to keep getting to this reality, whatever it took.

Labor would have to adapt and so would business.

Speaking to business — And staying right on it.

Coverage in Variety, an entertainment magazine founded in 1905 showed dialogues between business organizations and emerging studios were getting complicated.

The net was cast wide and all those in it came along.

While less technical than ACM, many of the articles in Variety dealt with patent battles, organizations, and inventors. Variety showed that there were negotiations not only between cinematographers and sound engineers but also between producers, executives, and the locations.

For example, in the July 9 edition of the paper, a short piece titled “Business Execs go, Harmony, when Mixing in Industrial Talker” cautioned producers from venturing too far off the east or west coast. 10 The article provided an example of a larger studio taking up a contract to film at a Pennsylvania Steel Mill.

As it turned out, the steel mill proved to be an unsuitable condition for photography, sound recording, and the crew, who were shipped to the steel mill, and ended up having their “going get ‘plenty tough.’” 16

As the excerpt below shows, producers had to shell out their own money.

“A steel mill is no studio, and the studio-trained technicians were confronted by obstacles to photography and sound recording. Result was that the producer finished the picture with part of his own dough.” 17

Clearly, newer studio-trained technicians worked best in sound stages, which despite being expensive, had become a necessity to save costs. Right from the flooring to the auxiliary equipment, the sound stage was as important as the recording devices in order to restore and extend, as Crafton calls them, “values developed in the silent motion picture.” 18 Whether newer cities offered spaces for filming or not, it was best to stay where the new sound film culture was emerging, more importantly, where both equipment and environment could work together.

A studio environment where technicians were comfortably trained with technology would benefit not only the workers but the business. We can see that producers not only had to understand the mechanics of production but also how to make the most efficient processes with it. They were now not only part of the network, but active investors in its success.

And this success would need to involve one more crucial piece — the fans.

Speaking to the fans about the sound man — “A god,” they said. “A god.”

Using a fan magazine as an artifact of representation assumes a form of mutual dependency between industry members and audiences; that is, a cyclical knowledge exchange. As film scholar Marsha Orgeron has pointed out, the film industry, the magazine publishing houses, and the fans all had “mutually dependent relationships”: one controlling, one mediating, and one supporting fans. 19

Photoplay, a prominent fan publication, did not hesitate to infuse a rather dramatic flair in their coverage of sound as a new technology. Writer Elaine Ogden penned a first-person piece titled “Inside the Monitor Room.” 20 She began by using descriptive language and situating the reader inside a monitor room, describing the elusive monitor man in rather regal language.

Two-page spread in Photoplay, a fan magazine in 1930.

“They call him a god around the studios,” wrote Ogden as an image of a man perched atop what looks like a studio can be seen on the left of figure above. The image in question took up a considerable portion of the page, with a caption that explicitly stated, “He is the uncrowned ruler of the studios, these talkie days.” 21

What this “mixer fellow,” as Ogden callously referred to him, had was a relationship to fate.

He was in control of the stars. “He has more power than the cameraman ever had,” she claimed. 22

Power? God? Fellow? Choice wording.

From a two-page spread in Photoplay, a fan magazine in 1930.

Ogden’s reference to the monitor room articulated a negotiated relationship between technological change, a new art form, an individual and celebrity culture. The Hollywood star would now be made or be broken by this new god. The new system needed a new character in control. And so the lore was created.

As journalist Pamela Hutchinson wrote in a Guardian article on January 26, 2016, Photoplay was known for its dramatic editorial voice so we should perhaps read its flair with a grain of salt. But what matters regardless is the role that fans played in the introduction of new technology. 23 They were more than fans, now actively invested in the production and development of the art form itself.

If Photoplay was created to provide “insider” access to the movie business, then Bazin’s argument for reproduction of reality not only involved the makers but very much the audiences. This reproduction of reality required a wider transacting.

The talkies had to become popular. They had arrived.

Network, network, network. We get it. But why does it matter?

In relation to the introduction of electric light in 1930s Moscow and Saint Petersburg, Russian formalist Victor Shklovsky states that the “new arrives unnoticed.” 11 He refers to how journalists at the time failed to report adequately on the staggering technological innovation. The new arrives unnoticed because we get acclimatized to habits, systems and processes. We miss what is right in front of us.

And once the new arrives, whether noticed or not, there is very little room for mitigation and negotiation.

Algae has always been about rendering the invisible, visible. By examining the nature of socio-technical systems as networked in the past, we allow for all the unnoticed parts to emerge in discourse.

From thereon, we can build and identify structures for the future.

It has always been about change.

What I hope is that somewhere in these examples, readers found insights on how we describe art and technology today — Perhaps it is in terminology like AI art or chatter around the game engine developer on a virtual production set or the possibility and also threat of generative AI as a replacement for filmmaking that we can remember how truly complex the adoption of these technologies are — and what to pay attention to.

Change does not happen overnight and it does not occur with only one vested party. Instead, it is sometimes slow and gradual, sometimes picking up pace and then slowing down again. It can be sneaky and overt, chaotic and clear but always occurring.

Perhaps like sound in cinema, the point is not to decide when and where the change has occured but to ask ourselves — what changes are we okay with? How can we read between the lines and what types of comparative frameworks can help us unpack subliminal messaging from the powers at be? What is the network being formed?

The power is with people.

Words like spatial computing, the metaverse, artificial intelligence, extended reality, virtual reality, virtual production and so on are, to me, the contemporary iterations of how new technological terminology is slowly but surely rolled out into popular lexicon.

It is perhaps wise to remember that regardless of whether we have total agency, partial agency or minimal agency, complete adoption will always remain a large, collective decision.

And through collective power, we must act.

Until next time.

Historial clippings of sound representations in 1930

1 Marvin, Carolyn. When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking about Electric Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century. Oxford University Press, 1988, pp. 5

2 Art Critic Jerry Saltz Gets into an Online Skirmish with A.I. Superstar Refik Anadol, link here.

3 De Sart, A. W. “Practical Aspects of Film Recording.” American Cinematographer Magazine, July 1930, pp. 12.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Marvin, Carolyn. When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking about Electric Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century. Oxford University Press, 1988, pp. 5

7 Glennon, Bert. “Cinematography and the Talkies: Some Honest Criticism by a Former Cameraman.” American Cinematographer Magazine, February 1930, pp. 7

8 Ibid.

9 Talkies is the name given to a film with a sound track, distinguishing it from silent cinema.

10 “Business Execs Go Harmony When Mixing in Industrial Talker.” Variety, July 1930, pp. 12–13.

11 Thorburn, David, and Henry Jenkins (eds.). 2003. Rethinking Media Change, The MIT Press, doi:10.7551/mitpress/5930.001.0001, pp. 44. Tom Gunning’s essay in this book introduced Victor Shklovsky’s formalism, connecting to media change. Link here.

12 ASC stands for the American Society of Cinematographers, a prestigious honorary organization founded in 1919 to advance the art and science of cinematography.

13 Clark, L. E., “Sound Stage Equipment and Practice: A Technical Digest Paper from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.” October 1930, pp. 15

14 Bazin, André, and Gray, Hugh. What is Cinema? Essays Selected and Translated by Hugh Gray. United States, University of California Press, 1967, pp. 166

15 Ibid. pp. 235

16 “Business Execs Go Harmony When Mixing in Industrial Talker.” Variety, July 1930, pp. 12–13.

17 Ibid.

18 Glennon, Bert. “Cinematography and the Talkies: Some Honest Criticism by a Former Cameraman.” American Cinematographer Magazine, February 1930, pp. 7

19 Orgeron, Marsha. “You are Invited to Participate’: Interactive Fandom in the Age of the Movie Magazine,” Journal of Film and Video, 61(1): pp. 19

20 Ogden, Elaine. “Inside the Monitor Room.” Photoplay, July 1930, pp. 76

21 Ibid. 76

22 Ibid. 76

23 Hutchinson, Pamela. “Photoplay Magazine: The Birth of Celebrity Culture.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 26 Jan. 2016, link here.

24 Crafton, Donald. The Talkies: American Cinema's Transition to Sound, 1926-1931. United Kingdom, University of California Press, 1999.

25 Clark, L. E., “Sound Stage Equipment and Practice: A Technical Digest Paper from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.” October 1930, pp. 15

26 Talkies is the name given to a film with a sound track, distinguishing it from silent cinema.